In the roiling national set-to over whether guns would make schools safer, most of the debate has been a caricature of itself. One side wants to install guns in every school, and the other wants to banish them. “I wish to God [the principal] had had an M-4 in her office, locked up,” Republican Representative Louie Gohmert of Texas said on Fox News after the Newtown, Conn., school massacre, “so when she heard gunfire, she pulls it out … and takes his head off before he can kill those precious kids.”

But the research on actual gunfights, the kind that happen not in a politician’s head but in fluorescent-lit stairwells and strip-mall restaurants around America, reveals something surprising. Winning a gunfight without shooting innocent people typically requires realistic, expensive training and a special kind of person, a fact that has been strangely absent in all the back-and-forth about assault-weapon bans and the Second Amendment.

(MORE: America’s New Gunfight: Inside the Campaign to Avert Mass Shootings)

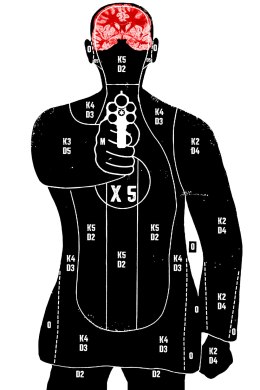

In the New York City police department, for example, officers involved in gunfights typically hit their intended targets only 18% of the time, according to a Rand study. When they fired 16 times at an armed man outside the Empire State Building last summer, they hit nine bystanders and left 10 bullet holes in the suspect—a better-than-average hit ratio. In most cases, officers involved in shootings experience a kaleidoscope of sensory distortions including tunnel vision and a loss of hearing. Afterward, they are sometimes surprised to learn that they have fired their weapons at all.

“Real gun battles are not Call of Duty,” says Ryan Millbern, who responded to an active-shooter incident and an armed bank robbery among other calls during his decade as a police officer in Colorado. Millbern, a member of the National Rifle Association, believes there is value in trained citizens’ carrying weapons for defensive purposes. He understands what the NRA’s Wayne LaPierre meant when he said, “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” But he knows from experience that in a life-or-death encounter, a gun is only as good as its user’s training.

(MORE: Cover Story: The Gunfighters)

Under sudden attack, the brain does not work the way we think it will. Millbern has seen grown men freeze under threat, like statues dropped onto the set of a horror movie. He has struggled to perform simple functions at shooting scenes, like unlocking a switch on a submachine gun while directing people to safety. “I have heard arguments that an armed teacher could and would respond to an active shooter in the same way a cop would. That they would hear gunshots, run toward the sound and then engage the shooter,” Millbern writes in an e-mail from Baghdad, where he now works as a bomb-detection K-9 handler. “I think this is very unrealistic.”

As lawmakers in at least seven states debate whether to allow teachers to carry firearms in school (something already allowed in Utah and Texas), it is worth considering: What happens in the human brain during a gunfight? And how much training would armed teachers or security guards need to prevail?

The Adrenaline Surge

At 3 p.m. one autumn day in 2004, Jim Glennon found himself being shot at without warning. He was a lieutenant, a third-generation cop who had decided on the spur of the moment to help out on a routine shoplifting call. The suspect, a white man in his mid-50s, had walked out of a liquor store with a bottle of vodka without paying for it, and the police had tracked his license plate to a condo complex in a suburb of Chicago.

The officers knocked on the door at the end of a long hallway and got no response. After a few minutes, Glennon started to suggest they come back with a warrant. That was when the man threw open the door and began firing a black snub-nosed revolver from three feet away.

Glennon was a police-academy trainer, unusually well schooled in survival skills. But from the moment he saw the revolver, his mind entered a state unlike anything he’d experienced before. “Oh s—! Gun!” he said, spinning his body hard to the left, missing a bullet by inches or less.

Without his conscious knowledge, the sight of the gun had sent a signal to his brain stem, passing a message to his amygdala—the primal, almond-shaped mass of nuclei that controls the fear response from deep within the brain’s temporal lobe. The amygdala, in turn, triggered a slew of changes throughout Glennon’s body. His blood vessels constricted so that he would bleed less if he got wounded. His heart rate shot up. A surge of hormones charged through his system, injecting power to his major muscle groups should he need to fight or flee.

His first actual thought was that the gun must have had only five or six rounds. He knew this because it reminded him of the revolver his grandfather gave his father years earlier. As he and a fellow officer turned and began racing down the hallway to take cover around the corner, he counted the number of shots he heard behind him, waiting for the suspect to run out of ammunition. Relying on his training, he pulled his .40-caliber Sig Sauer pistol out of his holster.

(FROM THE ARCHIVES: TIME’s Gun Covers, 1968-2013)

As happens for most people in life-or-death situations, his brain began to manipulate his perception of time, slowing down the motion as he fled down the corridor. “The hallway looked like one of those dreams where it is just really, really long,” he says. Later he would guess that it was 250 ft. long; it was really 79 ft.

But for each superpower his brain gave him, it took one away. In a flash, his brain reprioritized, shifting finite resources to the cause of survival. As he ran, rounds bursting behind him “like cannon shots,” he suddenly fell flat on his face in the carpeted hallway, tearing skin off his hands and knees.

“I was a 48-year-old guy wearing 20 lb. of equipment,” he remembers, “and I was running faster than I think my body was capable of handling.” In life-or-death situations, human beings often lose basic motor skills that we take for granted under normal conditions. (Attackers, not just those they’re shooting at, also experience such trade-offs, though they usually have the advantage of not being taken by surprise.)

Instantly, Glennon bounced back up and kept running to the corner, which seemed to get no closer with each step. Just then, his fellow officer fell down in front of him, screaming that he’d been shot. So Glennon’s brain reprioritized again. He grabbed the officer’s belt and heaved him the rest of the way around the corner. He remembers feeling pain in his back and thinking, Son of a bitch got me. It had taken seconds to get to the end of the hallway, but it felt like minutes.

Then, having finally taken cover, he turned and pointed back down the hallway toward the shooter. It was a chilling sensation to see his bare hand in front of him, pointing in the shape of a pistol like a boy on the playground. Where was his gun? “I looked at my hand. It wasn’t there. I looked in my holster. It wasn’t there.”

Without being aware of it, Glennon had dropped his gun in the hallway when he’d reached over to help the wounded officer. In moments of extreme stress, the brain does not allow for contemplation; it does not process new information the way it normally does. The more advanced parts of the brain that handle decisionmaking go off-line, unable to intervene until the immediate fear has diminished.