Luckily, Glennon did not dwell on this mistake. Nor did he freeze or shut down entirely, as many people do in life-or-death situations. Instead he reached over and grabbed the gun out of the holster of the injured officer. When he looked back down the hallway, he saw the arm of the shooter pointing toward him—and, behind it, the arm of a third police officer pointing out from another doorway.

More than anything else, Glennon wanted to shoot back. He started to squeeze the trigger. Then from somewhere in the recesses of his brain, he reminded himself: You can’t shoot. If he did, he would risk hitting the third officer standing behind the gunman. His training kicked in just in time, overriding his instincts.

The third officer took two shots at the gunman from an awkward angle, missing both times. But seconds later, the suspect threw his gun into the hallway, surrendering. The officers handcuffed him, and a battery of backup officers arrived. Glennon’s deputy chief ripped off Glennon’s bulletproof vest to make sure he hadn’t been shot too; he was fine. The pain in his back was the pain that came from one middle-aged man lifting another. Only later, in the ambulance, did Glennon begin to shake, just as he’d read people tend to do in the aftermath of an adrenaline surge.

Beyond Target Practice

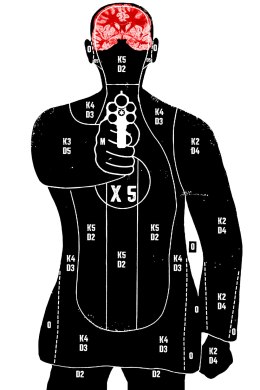

Today, Glennon runs Calibre Press, a law-enforcement training company based outside Chicago, and has trained tens of thousands of police officers nationwide. His primary message to his trainees is that they need better training than they typically get; real gunfights are nothing like the ones on TV. “Over half the police officers in the country are only required to go down once or twice a year and shoot holes in a paper target,” he says. Experts who study human performance in gunfights generally agree that people can train to perform better through highly realistic, dynamic simulation training. But that is expensive, especially compared with traditional target practice, and it doesn’t happen often enough.

(MORE: The Sandy Hook 26: Remembering Newtown’s Victims)

In the aftermath of the Newtown shootings, as local governments contemplate allowing more firearms in schools, Glennon worries that communities might inadvertently undertrain civilians just as they have done with police officers. “Cops aren’t trained well enough, so what do you think they’re going to do with teachers?” he says. “It’s not enough just to carry a gun.”

When I asked police safety experts how much training would be ideal for teachers or, for that matter, police officers assigned to schools, they offered different estimates. In Arizona, Alexis Artwohl, co-author of the book Deadly Force Encounters and a veteran police psychologist and trainer, recommended a weeklong program with “a lot of practice” and a requirement that participants meet minimum performance standards in order to graduate. In Ohio, Bill DeWeese, a veteran police officer and head of the National Ranger Training Institute, recommended two to three times that much training, and he pointed out that the best training includes much more than firing a gun. “I’m an avid firearms person and always have been,” he says. “The one thing I’ve learned is that it’s not about possessing firearms. It’s about possessing the skills to read a situation—learning how to adapt and maneuver, to respond to an unexpected, fluid situation.”

But in DeWeese’s state of Ohio, 1,100 teachers have already signed up for the Armed Teacher Training Program, offered free by Buckeye Firearms Foundation. That class will last just three days. In other states, civilians can get concealed-carry permits with one day of training or less. About a third of all public schools in the U.S. already have armed security, including every high school in Chicago, and that number may increase after the Newtown shootings. To date, there is no clear evidence that such measures make schools safer. Some studies have found a decrease in violence in schools with in-house police officers, while others have found no relationship at all. Still others have found that armed security makes some students feel less safe—and may funnel more students than necessary into the criminal-justice system for small infractions.

Of course, it’s also possible that the mere presence of armed teachers or guards could deter a shooter from attacking altogether. There would be no need to perform well in a gunfight—because there would be no gunfight. (Likewise, over the course of a career, it is statistically unlikely that a New York City police officer will ever fire his or her weapon in the line of duty, but the silent presence of officers’ weapons surely influences the behavior of civilians around them.) Many gun-rights advocates worry that gun-free school zones actually attract shooters because they represent easy, vulnerable targets. It’s hard to know, though, if mass murderers apply such logic when choosing targets—or if they simply seek to create the most socially abhorrent crime scenes in order to breed maximum shock and grief. In the case of the 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado, for example, the attacking students were aware that their school had an armed sheriff’s deputy in the school parking lot. (The deputy exchanged fire with one of them but missed.)

(TIME/CNN Poll: Obama’s Gun Plan Could Face Mixed Reception)

Of the mass shootings that are stopped by others, roughly two-thirds are brought to an end by civilians, according to Ron Borsch, a police officer and trainer in Bedford, Ohio, who has been keeping a database of such incidents since the Columbine shooting. That’s because they are typically the only ones in the immediate vicinity of the shooter. And most of those civilians are unarmed, Borsch has found. In the shooting of Arizona Representative Gabrielle Giffords and 18 others, which happened in just 15 seconds, civilians tackled gunman Jared Loughner, ripped the gun from his hands and confiscated his ammunition.

By then, though, it’s already too late for the victims. Dan Marcou, a former SWAT commander and police officer who was involved in three shootings in Wisconsin, argues that the public’s most important opportunity comes before any shooting starts. Most shooters belong to the communities they target and go through predictable phases before they kill anyone, from fantasizing about the murders to planning them. “We have to pay attention,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be a police officer who fires a shot; sometimes it’s a teacher who comes forward and says, ‘Hey, this guy is really dangerous.’”

By fixating on hypothetical school-yard gunfights, we are choosing to fight in the riskiest arena: the chances that an officer or armed educator will shoot a child by accident are high, as are the chances of arriving officers’ mistakenly shooting anyone seen with a weapon in the ensuing chaos.

With all this uncertainty, it is useful to remember that the odds of a U.S. student’s being killed at school are about 1 in 3 million, lower than the odds of being struck by lightning. Schools are safer now than they have been in 20 years. Kids do become victims of gun violence far too often in the U.S.—but almost always outside school, far from gun-free zones or teachers with pistols.