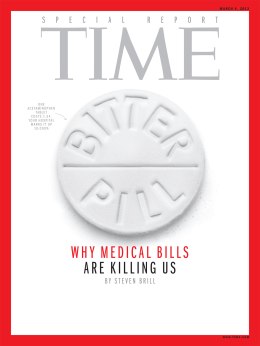

This article appears in this week’s magazine under the title, “Goodbye to the Surgical Mask.” It has been updated from the online version.

Our hospital bill is about to get a thorough examination. Acting on the suggestion of her top data crunchers at the department’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius released an enormous data file on May 8 that reveals the list—or “chargemaster”—prices of all hospitals across the country for the 100 most common inpatient treatment services in 2011. It then compares those prices with what Medicare actually paid hospitals for the same treatments—which was typically a fraction of the chargemaster prices.

As a result, Americans are a big step closer to being able to compare what hospitals charge them for goods and services with what they actually cost. CMS public-affairs director Brian Cook told me that Sebelius’ action today comes in part as a response to “Bitter Pill,” TIME’s special report on health care pricing practices in the March 4 issue.

(MORE: “Bitter Pill” Web Exclusives)

There are two reasons Sebelius’ release of this newly crunched, massive data file is a great first step toward a new transparency in health care costs.

First, it reveals the vast disparity between what hospitals charge for pills, procedures and operations and the real cost of those services, as calculated by Medicare.

As I explained in “Bitter Pill,” Medicare uses expense data submitted by all hospitals to determine the actual cost of all treatments—including allocations of overhead such as rent and administrative salaries—and pays accordingly. In other words, Medicare takes seriously—and enforces—the idea that nonprofit hospitals should be nonprofit.

For example, the first line in the more than 163,072 lines of data in the CMS file released May 8 covers the treatment of “extra cranial procedures” (“without complications”) at the Southeast Alabama Medical Center in Dothan, Ala. When Medicare reviewed the list prices on bills it received for 91 patients getting that treatment at the Dothan hospital in 2011, the average chargemaster bill claimed by the hospital was $32,963. Medicare paid only an average of $5,777.

The second reason the compilation and release of this data is a big deal is that it demonstrates the point I tried to make in spotlighting the seven sample medical bills in Time’s “Bitter Pill” report: most hospitals’ chargemaster prices are wildly inconsistent and seem to have no rationale. Thus the release of this fire hose of data—which prints out at 17,511 pages—should become a tip sheet for reporters in every American city and town, who can now ask hospitals to explain their pricing.

(VIDEO: Steven Brill on The Daily Show)

Helpfully, Sebelius points out in her announcement that “average inpatient charges for services a hospital may provide in connection with a joint replacement range from a low of $5,300 at a hospital in Ada, Oklahoma, to a high of $223,000 at a hospital in Monterey Park, California. Even within the same geographic area,” she notes, “hospital charges for similar services can vary significantly. For example, average inpatient hospital charges for services that may be provided to treat heart failure range from a low of $21,000 to a high of $46,000 in Denver, Colorado, and from a low of $9,000 to a high of $51,000 in Jackson, Mississippi.”

The hospital lobby, led by the American Hospital Association, is going to howl that Sebelius’ publication of these chargemaster prices is unfair. Only a minority of patients are actually asked to pay those amounts, it will argue. Insurance companies, which cover the majority of patients, receive huge discounts off the list prices, though they pay substantially more than Medicare does.

That’s true, but in the through-the-looking-glass world of health care economics, those who are asked to pay chargemaster rates are often under-insured or lack insurance altogether. Moreover, insurers typically negotiate discounts off the grossly inflated chargemaster prices ($77 for a box of gauze pads!), so the chargemaster matters for insured patients too.

So what should Sebelius and her team do next?

The feds need to publish chargemaster and Medicare pricing for the most frequent outpatient procedures and diagnostic tests at clinics—two huge profit venues in the medical world. But an even bigger step toward transparency would be collecting data that Medicare doesn’t have: exactly what insurance companies pay to the various hospitals, testing clinics and other providers for various treatments and services.

After all, as the hospitals themselves concede in downplaying their chargemasters, these insurance prices are the ones that affect most patients.

And that is one price list where there is close to zero transparency.

Click here for an excerpt from “Bitter Pill.” To read the full special report, subscribe here to TIME.