Eager to be eyewitnesses to history, people camped for days in the dismal cold, shivering in the slanting shadow of the Capitol dome, to claim tickets for the Supreme Court’s historic oral arguments on same-sex marriage. Some hoped that the Justices would extend marriage rights; others prayed that they would not. When at last the doors of the white marble temple swung open on March 26 for the first of two sessions devoted to the subject, the lucky ones found seats in time to hear Justice Anthony Kennedy — author of two important earlier decisions in favor of gay rights and likely a key vote this time as well — turn the tables on the attorney defending the traditionalist view. Charles Cooper was extolling heterosexual marriage as the best arrangement in which to raise children when Kennedy interjected: What about the roughly 40,000 children of gay and lesbian couples living in California? “They want their parents to have full recognition and full status,” Kennedy said. “The voice of those children is important in this case, don’t you think?” Nearly as ominous for the folks against change was the fact that Chief Justice John Roberts plunged into a discussion of simply dismissing the California case. That would let stand a lower-court ruling, and same-sex couples could add America’s most populous state to the growing list of jurisdictions where they can be lawfully hitched.

A court still stinging from controversies over Obamacare, campaign financing and the 2000 presidential election may be leery of removing an issue from voters’ control. Yet no matter what the Justices decide after withdrawing behind their velvet curtain, the courtroom debate — and the period leading up to it — made clear that we have all been eyewitnesses to history. In recent days, weeks and months, the verdict on same-sex marriage has been rendered by rapidly shifting public opinion and by the spectacle of swing-vote politicians scrambling to keep up with it. With stunning speed, a concept dismissed even by most gay-rights leaders just 20 years ago is now embraced by half or more of all Americans, with support among young voters running as high as 4 to 1. Beginning with the Netherlands in 2001, countries from Argentina to Belgium to Canada — along with nine states and the District of Columbia — have extended marriage rights to lesbian and gay couples.

True, most of the remaining states have passed laws or constitutional amendments reserving marriage for opposite-sex partners. And Brian Brown, president of the National Organization for Marriage, declares that the fight to defend the traditional definition is only beginning. “Our opponents know this, which is why they are hoping the Supreme Court will cut short a debate they know they will ultimately lose if the political process and democracy are allowed to run their course,” he said.

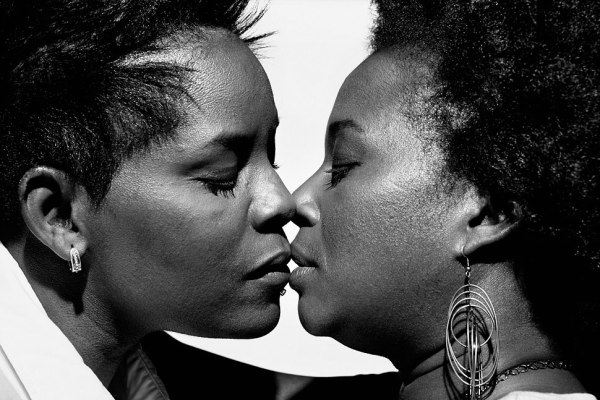

(MORE: Behind TIME’s Cover Photos — Portraits of the Gay Marriage Revolution)

But that confidence is rare even among the traditionalists. Exit polls in November showed that 83% of voters believe that same-sex marriage will be legal nationwide in the next five to 10 years, according to a bipartisan analysis of the data. Like a dam that springs a little leak that turns into a trickle and then bursts into a flood, the wall of public opinion is crumbling. That’s not to say we’ve reached the end of shunning, homophobia or anti-gay violence. It does, however, suggest that Americans who are allowed by law to fall in love, share their lives and raise children together will, in the not too distant future, be allowed to get married.

Through 2008, no major presidential nominee favored same-sex marriage. But in 2012, the newly converted supporter Barack Obama sailed to an easy victory over Mitt Romney, himself an avowed fan of Modern Family — a hit TV show in which a devoted gay couple negotiates the perils of parenthood with deadpan hilarity. When even a conservative Mormon Republican can delight in a sympathetic portrayal of same-sex parenthood, a working consensus is likely at hand.

Down the ballot, elected leaders who once faithfully pledged to protect tradition have lined up to announce their conversions. Republican Senator Rob Portman of Ohio said he changed his mind after learning that his son is gay. Red-state Democrats Claire McCaskill of Missouri and Jon Tester of Montana, both skilled political tightrope walkers, also switched, as did Virginia’s Mark Warner. They joined Hillary Clinton and her husband, the former President who signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law during his 1996 re-election bid but is now calling on the Supreme Court to undo his mistake.

(MORE: Watching Kennedy: The Court’s Swing Voter Offers Clues to a Gay-Marriage Ruling)

Such switchers have plenty of company among their fellow citizens. According to a recent survey by the Pew Research Center, 1 in 7 American adults say their initial opposition to same-sex marriage has turned to support. The picture of a nation of immovable factions dug into ideological trenches is belied by this increasingly uncontroversial controversy. Yesterday’s impossible now looks like tomorrow’s inevitable. The marriage license is the last defensible distinction between the rights of gay and straight couples, Cooper told the Justices as he steeled himself to defend that line. But most generals will tell you that when you’re down to your last trench, you are likely to lose the battle.

What’s most striking about this seismic social shift — as rapid and unpredictable as any turn in public opinion on record — is that it happened with very little planning. In fact, there was a lot of resistance from the top. Neither political party gave a hint of support before last year, nor was marriage part of the so-called homosexual agenda so worrisome to social-conservative leaders. For decades, prominent gay-rights activists dismissed the right to marry as a quixotic, even dangerous, cause and gave no support to the men and women at the grassroots who launched the uphill movement.