Letting some military units march in place—not immediately ready for war—would save billions.

The Navy just christened a $13 billion aircraft carrier, up 22% from its 2008 estimate. Outsiders predict the Air Force’s new bomber could cost 47% more than the service is planning to spend. The Army is thinking of replacing its tiny OH-58 Kiowa scout helicopters with brawny AH-64 Apache gunships, a switch that would have driven up the cost of scout-chopper operations by $4 billion in Afghanistan and Iraq.

When you’re spending money like this on shiny hardware, it’s tough to cut spending. That’s one of the reasons Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel told the military services last month that “some kind of a tiered-readiness system is perhaps inevitable.”

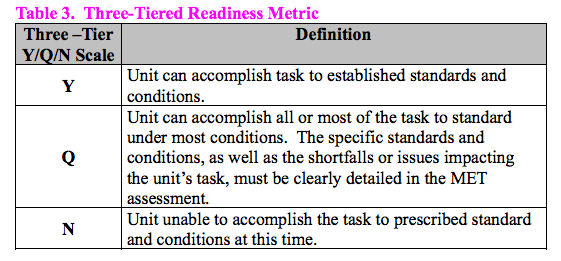

“Tiered readiness” are fighting words inside the Pentagon. Any savings realized by having, for example, three official budgeted levels of readiness—let’s call them Yes, Qualified, and No, like they do at the Pentagon—would be illusory, defense officials maintain. That’s because of the need to keep surge capabilities in place to generate ready forces if a major conflict suddenly erupted.

Uniformed officers view tiered readiness it as a precursor to a “hollow military.” That phrase evokes the post-Vietnam U.S. military that ended in humiliation and the death of eight U.S. troops in the crashed-and-burned U.S. effort to rescue 52 Americans held in Iran in 1980. They maintain that if you’re going to pay for 100 tanks, or warplanes, or ships, you’re wasting money if they’re not all primed for war.

Of course, it has never been that stark. Military units are at their sharpest—most ready—when they deploy, and come home from war or peacetime deployments ragged. Then, over a span of months, they spin up their readiness rates through training and re-equipping.

The topic last came up in the late 1990s, but went nowhere. “Such `tiering’ would significantly increase risk at the gain of only modest savings while limiting the flexibility required to execute the current war plans,” the Pentagon’s Quadrennial Defense Review, which puts the status in status quo, concluded in 1997. “Constraining factors include the time when units are required to be in theater, the difficulty in regaining the highly perishable skills required to operate sophisticated weapon systems, the capacity of the training infrastructure, the need to optimize match-up of deploying units with transportation assets, and the requirement to adjust plans based on the strategic and tactical situations.”

A student at the Pentagon’s National Defense University summed up the military’s opposition like this in 1998:

Tiered Readiness sends shivers up the spine of military people who survive the Hollow Force era of the 70’s. A Tiered Readiness program is likely to be met with exceptionally strong resistance from the military establishment. Besides dislike for the concept, Tiered Readiness would require a level of sophistication in readiness reporting and planning the military cannot provide.

Apparently, the Pentagon’s classified reporting system has improved, and Hagel is willing to consider tiered readiness. He is acknowledging the obvious: the nation can cut its military more deeply than current plans call for, to ensure the remainder is fully ready. Or it can make explicit that keeping all units always ready is costly. Budget cuts of about $1 trillion over a decade, about 10%, are pushing him to consider that second route.

Readiness levels already are falling, defense officials say, as budget cuts over the past nine months have led to reduced training and delayed maintenance. Readiness accounts for about a third of military spending, or roughly $200 billion annually.

“Tiered readiness” means different things to different services, as General Mark Welsh, the Air Force chief of staff, explained recently. Both the Army and Navy can get by with some brigades and carriers being less than fully ready for war because, he said, they have more than enough tanks and warships—and the people to operate them—to fulfill current war plans.

But his service is different. “In the Air Force, if you look at our force structure…the demand signal equals our force structure,” Welsh said. “We could buy twice as much force structure and have a tiered-readiness model, which would make no sense because the force structure costs a lot more than the readiness costs…we want to keep it 100% ready.” But the current budget crunch has left Air Force warplanes less than 40% ready, Welsh said.

The Marines are taking no prisoners on the subject. “`Tiered readiness’ amongst non-deployed Marine units is unacceptable,” General James Amos, the commandant, told Congress in September. “Over time, tiered readiness creates a hollow force.”

The Navy, which predictably cycles its ships to sea whether at war or not, is less affected by a tiered-readiness scheme.

The Army concedes tiered readiness is already infecting its ranks. Under current budget caps, 85% of its brigade combat teams will be less-than-fully ready by next Oct. 1. “We’re going to have to severely tier our readiness,” General Ray Odierno, the chief of staff, has told lawmakers. “My biggest fear, actually what keeps me up at night, is I’m asked to deploy soldiers on some unknown contingency and they are not ready.”

The bottom line is simple, although not yet much discussed: how big of a war should the nation be prepared to wage from a standing start? How much risk is acceptable in not being able to do that? Until that question is thoroughly debated and the resulting marker set, we have no way of knowing if we’re dangerously unready, or simply broke.