The main pieces of a blown apart B-1 bomber set fire to Montana pastureland last August.

A sign in World War II’s Anglo-American Supply headquarters in London displayed the adage that begins with “For want of a nail, the shoe was lost.” It quickly marches through several increasingly larger military problems, each triggered by the one that came before. It ends with “For want of a battle, the kingdom was lost.”

While the crash of a $318 million B-1 bomber last August 19 in Montana has no parallel to that war, the sentiment—that a little military snafu can quickly mushroom into a series of ever-growing disasters—is spot on.

Come along, if you dare, for the ride…

Call sign Thunder 21 took off from Ellsworth Air Force Base, outside Rapid City, S.D., last August 19 at 8:57 a.m. The sky was blue and visibility was unlimited as the highly-experienced four-man crew headed west to the Powder River bomb range for their first bombing run since returning from missions over Afghanistan. Major Frank Biancardi II was in charge, aided by co-pilot Captain Curtis Michael. Sitting just behind them were weapons systems captains Chad Nishizuka and Brandon Packard.

Eight minutes later, the Rockwell-built Thunder 21 (now part of Boeing) began to descend from 20,000 to 10,000 feet as the B-1 approached the bombing range. Powder River’s 8,300 square miles makes it about the size of Massachusetts. It straddles northwestern South Dakota, northeast Wyoming and southeast Montana, and ranks among the nation’s least populated areas.

Biancardi ordered the plane, in a neat display of technological wizardry, to sweep its main wings back from their forward 25-degree angle to their swept 67.5-degree position. The variable-sweep design allows for boosted lift at takeoff (with a maximum 137-foot wingspan), but reduces drag and allows higher speeds during low-altitude attacks (with a more streamlined 79-foot wingspan).

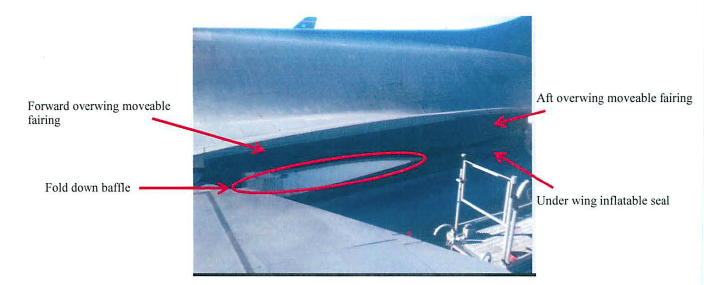

As the left wing slowly swung back, it pushed a metal seal—designed to ensure smooth airflow over the variable wing—where it shouldn’t go. For reasons investigators couldn’t determine, the seal had come loose.

Oblivious to the slow-motion debacle unfolding just outside their cockpit, the crew concentrated on their mission as the wing slowly pushed the seal toward the 4.5-inch braided fuel line that feeds the pair of huge General Electric engines, each capable of generating 30,000 pounds of thrust, slung underneath the wing.

As the wing gradually swept back, the seal and what investigators called its “acute, v-shaped angle at the aft end” drew closer to the fuel line. Think of it as a slow-motion ax aimed at a hose throbbing with jet fuel. About thirty seconds after the sweep started, the seal—officially called an “underwing fairing fold down baffle”—pushed into, and sliced open, the top half of the fuel line.

The plane had became a supersonic Old Faithful, spewing 120 gallons of highly-explosive aviation fuel every minute.

The crew continued its mission enveloped in the comfort only ignorance provides. The plane dropped to about a thousand feet for its bombing mission, and began a left-hand turn after one of the backseat weapons operators detected a simulated threat.

But the true threat was now sloshing through assorted compartments and chambers of the B-1’s left wing. Eight minutes after the slicing, there would be 1,000 gallons of fuel spilled from the sliced hose, with some of it running along the left wing and some streaming down the left side of the plane its crews affectionately call the Bone (for B-one).

When the fuel finally contacted a hot duct inside the left wing, it exploded, blowing part of the wing from the aircraft and sending the plane into a left bank. The crew felt what they described as a “violent” explosion, followed by a warning light and alarm indicating a wing fire. They quickly activated the wing’s main fire-suppression system, designed to discharge 90% of its suppressant within a second and choke off the oxygen the fire needs to burn.

But still protected by the grace only unawareness can offer, the crew already was beyond the point of no return. They couldn’t see the fuel turning into a huge flame behind them, generating a 300-foot fiery torch erupting from the 146-foot-long plane. The unseen flames were toasting the left side of the B-1’s fuselage—and one of the plane’s several fuel tanks, just inches away.

Ninety seconds after the first explosion, the Engine 2 fire light illuminated in the cockpit. A second later, the Engine 1 fire light came on. Biancardi ordered the B-1 to climb, and begin turning for an emergency 150-mile trip back to Ellsworth.

Thirty seconds later—after the main fire-suppression system seemed to have failed to extinguish the fire—co-pilot Michael activated the reserve fire-suppression system. But with pieces of the wing now missing, the suppressant—free to discharge into the sky—was worthless.

Then there was a second, deafening blast.

That fuselage-licking torch heated the vapors in the nearby fuel tank to 437 degrees Fahrenheit (225 degrees Celsius), the point when jet fuel automatically ignites. Within moments, the flaming vapors flashed through the B-1’s fuel-venting system, setting off “a cascade of catastrophic explosions,” in the words of the Air Force’s recently-released official investigation into the crash (Part 1 here; Part 2 here).

The crew had no idea what was happening. Far below, Chris Gnerer, a dirt-bike-riding rancher on his 2,000 acres of southeastern Montana, was an eyewitness. According to the Rapid City Journal:

He was searching for stray cattle around 9 a.m. when an orange flame caught his eye. Gnerer turned to see an object explode in mid-air about seven miles away.

Back in the B-1 cockpit, the controls went dark—the aircraft had lost all power. The plane pitched into into a leftward-rolling dive. “The rupturing of the mishap aircraft’s fuel tanks resulted in the severing of the electrical cables running through the tops of the fuel tanks,” the report found, “causing a complete and permanent loss of electrical power in the crew compartment.”

The power loss left the crew with no other option: the airmen had to eject. They left their aircraft at 10,700 feet above the ground while traveling at 460 miles an hour. A moment later, the B-1 fuselage split in two, along the perforations caused by the series of fuel-tank explosions.

Back on the ground, according to the Journal:

Gnerer was awestruck as he watched the object split into two flaming pieces. One exploded in a mushroom cloud on a neighboring ranch. The other quickly joined it, producing a matching cloud. Panicking, Gnerer called his wife. Krista Gnerer, a part-time nurse, was working in a town about 30 miles away that day. Gnerer told her he had seen something — a comet, a piece of the sun, just something — fall from the sky. He thought the world might be ending.

Back in the sky, “the helmets of all four crewmembers came off during the ejection sequence,” the crash report said. “Although the helmets appeared to be properly configured, each helmet had multiple failures, likely caused by windblast during the ejection sequence.” All four parachuted to safety with relatively minor injuries.

Thunder 21’s remains fell across 17 miles of pastureland some 24 miles east of Broadus, Mont. Gnerer helped rescue the downed airmen, who had to wait two hours for an ambulance to arrive at their desolate location.

The accident has several lessons, for both weapons and war-fighters.

First, K.I.S.S.—“keep it simple, stupid.” That’s another tried and true military saying. There’s a reason the B-1 is the last warplane in the U.S. military inventory with variable-sweep wings and the hazards their operation can pose.

Second, never underestimate the skill of a well-trained crew.

Third, for every airman, soldier, sailor or Marine in harm’s way, there’s a family somewhere holding its breath.

Captain Nishizuka’s older brother, Reid, died last April when his MC-12 spy plane crashed in Afghanistan, as detailed in this TIME report. Chad Nishizuka escaped the B-1 crash with only a dislocated shoulder.

Their father said he couldn’t believe it when he learned of his younger son’s near-death experience less than four months after his older son perished. “My heart just stopped,” Ricky Nishizuka told a Hawaiian reporter.

Why did Chad live? “This whole ordeal has made me believe in guardian angels,” their father said. “I really believe his brother was there to take care of him.”