A U.S. contractor directs traffic in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Contractor fraud and waste in Afghanistan and Iraq has run rampant, costing U.S. taxpayers something between $31 billion and $60 billion, according to the congressionally created Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But it also has cost many of those contractors too: a new report from the Rand Corp. says such private workers suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder and depression at rates similar, if not higher, than the troops they serve alongside.

The Rand study, Out of the Shadows: The Health and Well-Being of Contractors Working in Conflict Environments — released Dec. 10 as part of what Rand describes as “self-initiated independent research” — says:

Although contractors have become a nontrivial part of the fighting force in several theaters of conflict over the past decade, their characteristics, deployment experiences, and health status have not been thoroughly explored. This study found that the contractors sampled have similar deployment experiences to military personnel—including combat exposure. The contractors in our study reported relatively high rates of probable mental health problems, including PTSD and depression. Moreover, our findings suggest that this population has few resources to cope with these problems and faces significant barriers to seeking mental health treatment.

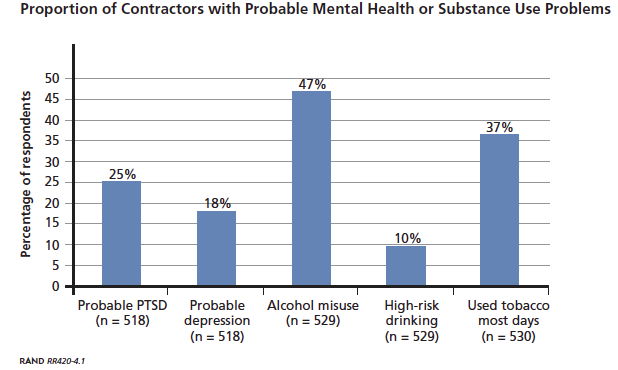

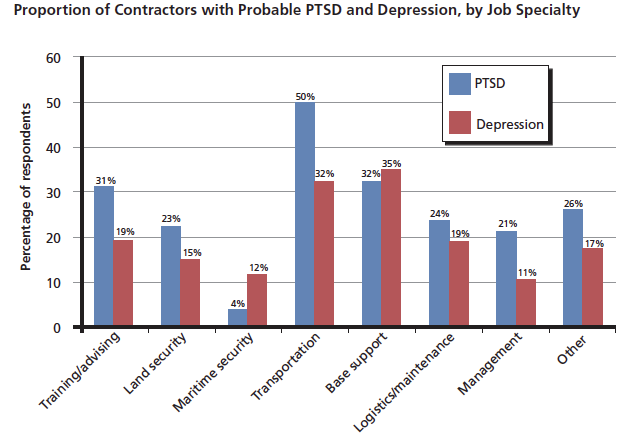

“The proportion of contractors who met criteria for PTSD or screened positive for depression was notably higher than that among military populations,” the Rand study concludes. One in four contractors surveyed probably had PTSD, the report says, but that rate doubled — to a sky-high 50% — for those operating convoys, “most likely due to greater combat exposure,” including ambushes and roadside bombs. Eighteen percent screened positive for depression and half reported abusing alcohol. Rand researchers conducted an anonymous online survey of 660 workers, nearly two-thirds of them American, who deployed at least once between 2011 and 2013. It marks the first survey of such contractors.

“The psychological health of contractors has long been a festering, half-hidden issue,” says Elspeth Ritchie, a retired Army colonel who served as the service’s top psychiatrist. “Little has been done to address it, but this Rand report does an admirable job of detailing the problem.”

Coming up with an apples-to-apples comparison of rates of mental ills between contractors and troops is challenging because of variations in measuring and methodology, Rand says. But among U.S. troops deployed to the post-9/11 wars, PTSD afflicts an estimated 4% to 20%; depression is estimated between 5% and 37%; and alcohol misuse ranges from an estimated 5% to 39%.

Contract personnel can be a bargain: unlike troops, they generally are not entitled to government-funded help for any mental ailments that may have been triggered, or aggravated, by their civilian service. “There is a significant unmet need for health care, with only 28% of those with probable PTSD and 34% of those with probable depression receiving mental health treatment in the 12 months prior to the survey,” the report says. “Mental health problems, especially probable PTSD and depression, are of particular concern, and many contractors are not getting the treatment they need.” (But 84% of the contractors surveyed had military experience, suggesting they could seek help as veterans.)

During the wars’ peak, contractors outnumbered those in uniform: in 2008, there were 155,826 Pentagon-hired contractors alongside 152,275 U.S. troops in Iraq in 2008. In 2010, there were 94,413 contractors in Afghanistan, along with 91,600 American troops. “Seventy-three percent of respondents,” Rand says, “reported that they or members of their team were exposed to hostile incoming fire from small arms, artillery, rockets, mortars, or bombs … 48% reported that they or a member of their team had been attacked by terrorists or civilians.” The contractors served in a variety of support roles, including logistics, maintenance, transportation, intelligence, communications and security. More than 1,600 have been killed (259 in Iraq, 1,378 in Afghanistan, as of April).

“Given the extensive use of contractors in conflict areas in recent years,” co-author Molly Dunigan says, “these findings highlight a significant but often overlooked group of people struggling with the aftereffects of working in a war zone.” Over the past six years, the $160 billion the U.S. spent hiring contractors in Afghanistan and Iraq topped the total contract obligations of any other U.S. government agency.

Contractors are not supposed to engage in offensive combat, the Rand report notes. But “contractors who carried a weapon [2 of every 3 surveyed] felt better prepared for deployment than those who did not,” it adds. But the bar on combat doesn’t protect them from experiencing “gunfire, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and other modes of attack; serious injury; kidnapping; the deaths of fellow personnel; and the psychological aftermath of killing.”

The fact that contractors serving alongside soldiers are suffering from many of the same mental ailments shouldn’t come as a surprise. It stems from a Pentagon effort to reduce the number of troops deployed to war zones by shifting many jobs that they used to do — ranging from security to cooking — to hired help.

That way, Pentagon officials could declare there were 150,000 U.S. troops in Iraq in 2008, instead of the 300,000 personnel actually there, waging war at the U.S. government’s behest, and on the taxpayer’s dime.