When push came to shove for the U.S.-led military efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq, some experts urged the adoption of a so-called “oil-spot strategy” as a way of doing more with less. Instead of placating the entire nation all at once, it called for the establishment of small, secure areas that would gradually grow over time as counter-insurgency successes in the initial zones oozed outward and ultimately connected.

It made sense, at least at first glance. But now, a key monitor of U.S. success in Afghanistan is warning that the opposite is, in fact, happening: more and more of Afghanistan is becoming insecure as the U.S. and its allies leave the country. In other words, the “oil spots” are shrinking, surrounded by growing areas of instability.

Bottom line: the U.S. strategy of securing more of Afghanistan seems to have worked only so long as U.S. troops were on the ground to secure it. The handoff of security to Afghanistan hasn’t taken root, and the nation is becoming less secure as the U.S. pulls out.

In a recent letter to Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel and Secretary of State John Kerry, released Monday, a top independent Pentagon auditor says that the slice of Afghanistan his overseers can visit is shrinking as concerns for their safety mount.

“U.S. officials have told us that it is often difficult for program and contracting staff to visit reconstruction sites in Afghanistan,” John Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, wrote. “U.S. military officials have told us that they will provide civilian access only to areas within a one-hour round trip of an advanced medical facility. Although exceptions can be made to this general policy, we have been told that requests to visit a reconstruction site outside of these ‘oversight bubbles’ will probably be denied.”

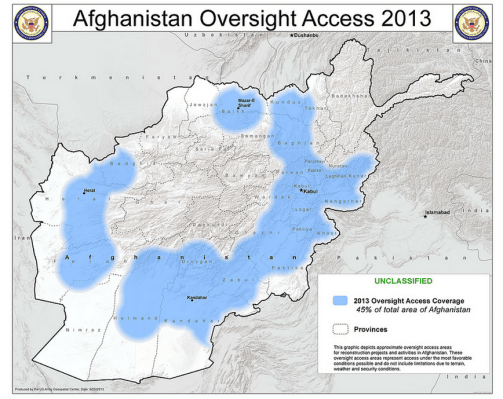

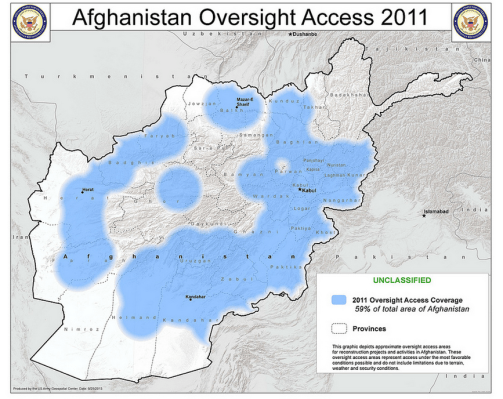

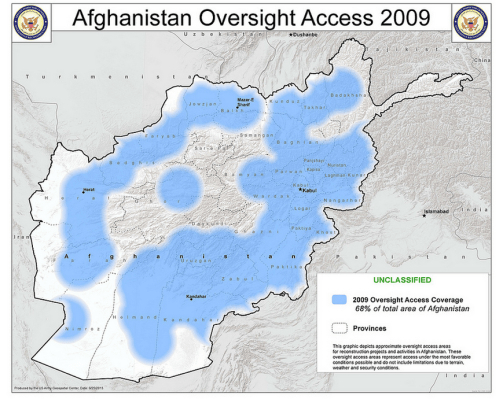

Sopko included maps of Afghanistan showing the shrinking safe zones inside the country. “Although it is difficult to predict the future of the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, it is likely that no more than 21 percent of Afghanistan will be accessible to U.S. civilian oversight personnel by the end of the transition,” he said of the 2015 deadline for all U.S. combat troops to withdraw. “We have also been told by State Department officials that this projection may be optimistic, especially if the security situation does not improve.”

Sopko’s maps are basically an indicator of the extent of security around Afghanistan, drafted by the Army’s Geospatial Center based on data from the Pentagon and State Department. The maps, he added, show “a best-case scenario where weather, terrain, and security conditions pose no serious threat to helicopter medical evacuation missions.” The maps show the area of Afghanistan deemed safe for federal auditors to visit has fallen from 68% in 2009 to an estimated 21% in 2014.

Retired Army lieutenant colonel Andrew Krepinevich popularized the oil-spot notion in a 2005 article in Foreign Affairs, during the darkest days of the U.S.-led alliance in Iraq. “Since the U.S. and Iraqi armies cannot guarantee security to all of Iraq simultaneously, they should start by focusing on certain key areas and then, over time, broadening the effort — hence the image of an expanding oil spot,” wrote Krepinevich, who heads the non-profit Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

The concept caught on as a way to wage war with too-few troops. “The oil spot, if you will, is a term in counterinsurgency literature that connotes a peaceful area, secure area,” Army General David Petraeus told NBC in 2010 when he commanded the Afghan effort. “What you’re trying to do is to always extend that, to push that out. Of course, down in Helmand Province what we sought to do was to build an oil spot that would encompass the six central districts of Helmand Province, including Marjah and then others, and then to just keep pushing that out, ultimately to connect it over with the oil spot that is being developed around Kandahar City.”

Sopko, who said his staff couldn’t visit reconstruction projects costing $72 million in northern Afghanistan earlier this year because of safety concerns, said steps should be taken to ensure access to such sites. The U.S. Agency for International Development may hire monitors to keep an eye on such work, he said, and the State Department is studying the wisdom of occasionally deploying security and medical teams to the edges of “oversight bubbles” as a way of making them bigger, at least temporarily.

“Even if these alternative means are used to oversee reconstruction sites, direct oversight of reconstruction programs in much of Afghanistan will become prohibitively hazardous or impossible as U.S. military units are withdrawn, coalition bases are closed, and civilian reconstruction offices in the field are closed,” Sopko warned.

Since invading Afghanistan on Oct. 7, 2001 — in retaliation for the safe haven the Taliban government provided Osama bin Laden to plot the 9/11 attacks — the U.S. has spent close to $100 billion on reconstruction efforts inside the country:

— $54.30 billion for security

— $24.70 billion for governance and development

— $6.92 billion for counter-narcotic efforts

— $2.67 billion for humanitarian aid

— $7.99 billion for operations and oversight

The war’s total cost to U.S. taxpayers is approaching $700 billion, and, to U.S. families, 2,191 lives.