A Navy sailor on the carrier U.S.S. Enterprise readies bombs for delivery to Iraq during Desert Fox in 1998

While the U.S. is trying to cobble together a coalition of the willing to give some legal cover for attacking Syria, American military planners are fine-tuning a playbook that at first glance may look a lot like Operation Desert Fox, a four-day bombing campaign against Iraq’s elusive weapons of mass destruction in 1998.

Tactically, that is.

Operation Jasmine Jolt, or whatever the Pentagon ends up calling the looming limited strike against Syria (Damascus has long been known as the City of Jasmine), will go after much different targets — and a different goal — from Desert Fox.

That’s a good thing for the Obama Administration. It should give the White House a chance to review bomb-damage assessments and declare that its goal of punishing Syrian dictator Bashar Assad for his alleged use of chemical weapons has been achieved — something the Clinton Administration couldn’t do, following its inconclusive bombing of Iraq.

Here’s how the barrages are likely to be the same:

- Like Desert Fox, the trigger will be weapons of mass destruction. The Iraqi bombing was aimed at crippling Iraq’s WMD production following a long-running cat-and-mouse game between Saddam Hussein and U.N. weapons inspectors. The Syria attack would be to punish Damascus for what the U.S. is calling its “indiscriminate” use of chemical weapons in suburbs of the Syrian capital that killed hundreds of civilians.

- Like Desert Fox, the U.S. will lead the attack with air strikes. In this case — to avoid risking American pilots — the four Navy destroyers now lurking in the eastern Mediterranean Sea will lob cruise missiles toward Syrian targets. If President Obama wants to hit Syria harder, warplanes with bigger bombs — perhaps B-2s flying round trip from their Missouri base, or short-legged attack planes in the region — could see action.

- Like Desert Fox, the most important ally in the attacks will be Great Britain. France — a leader in backing the rebels seeking to overthrow Assad — will also play a military role. To keep the operation from being an all-Western show, Arab allies will be encouraged to participate.

An F-18 prepares to attack Iraq from the carrier U.S.S. Enterprise during Desert Fox

More important, however, here is how any attack on Syria would likely differ from 1998’s attack on Iraq:

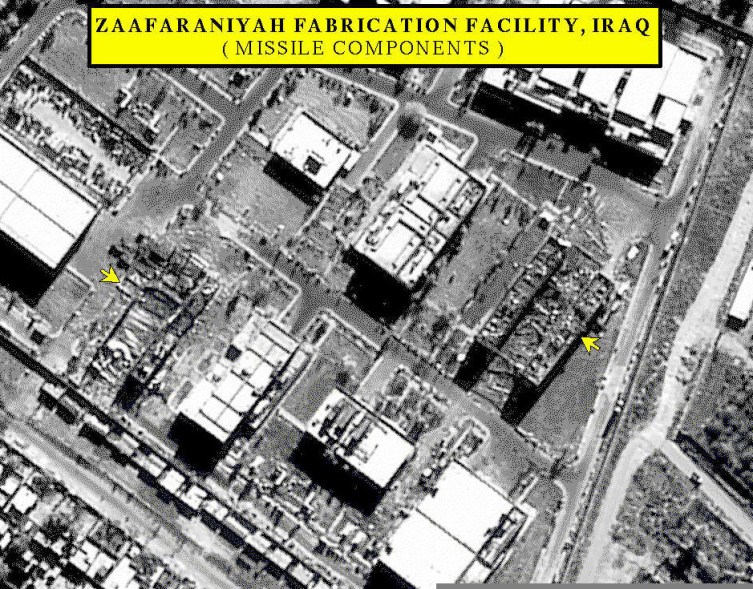

- While both are rooted in weapons of mass destruction, the U.S. and its allies will not target them in Syria. Instead, they’ll go after the enablers — command posts, communications nodes, troops and delivery systems like missile launchers and artillery tubes — that Assad’s government needs to use them.

“It’ll probably be aimed at Syria’s command-and-control systems, the forces who might have been involved in using it, and maybe expanded to include higher headquarters that would have coordinated the operations,” says Jeffrey White, a former Defense Intelligence Agency analyst now with the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “I don’t think we want to get into the business of trying to degrade his chemical weapons, but we can degrade and punish the forces that were involved.”

- It’s a lot easier to declare “mission accomplished” when your objective is to blow up command posts, weapons depots and runways, instead of hunting down and destroying weapons of mass destruction, which can be elusive.

Anthony Zinni, who as a four-star Marine general commanded Desert Fox, knows the frustrations that can come from hunting down weapons of mass destruction — especially chemical and biological weapons, which often depend on the same “dual-use” production infrastructure as many legitimate industries.

“There was one problem with Desert Fox — Washington believed we were going after his weapons-of-mass-destruction program,” Zinni says. “But when I looked at the [CIA-provided] target list, there was nothing there that was specifically part of a weapons-of-mass-destruction program; they were all ‘possible’ parts.”

That led to miscommunication. Then Army general and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs “Hugh Shelton called me up and said, ‘The President [Bill Clinton] wants to know how far back you can set back Saddam’s program with a strike,'” Zinni recalls.

Zinni’s staff calculated that taking out the targets on the CIA’s list would set back Iraq’s work related to them by two years. “By that, I meant we could destroy the machinery, his short-range-missile program” and other targeted sites, Zinni recalls. “But in Washington, that got translated into ‘We set back his program two years.’ But there was no [WMD] program.”

- The impending strike on Syria, unlike Desert Fox, might actually work.

There will be claims from Syria of innocent civilians killed (Desert Fox killed up to 2,000 Iraqis) and complaints from Syrian allies Iran and Russia that the strikes violated international law, predicts Anthony Cordesman, a military scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But, at the end of it,” he says, “they probably won’t use chemical weapons again.”

That may be the good news, relatively speaking. The bad news is that there’s no idea of what comes next for Syria, already torn apart by a 30-month civil war that has killed an estimated 100,000 people, after the all-but-certain U.S. attack.