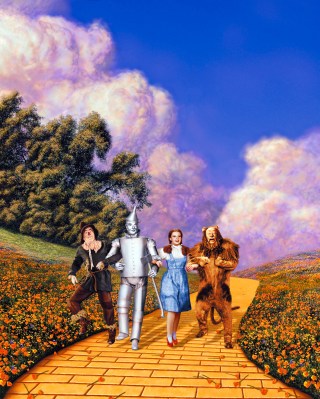

Arthur Laffer testifies before the Kansas House Tax committee at the statehouse, Thursday, Jan. 19, 2012 in Topeka, Kansas.

In the statehouses of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri, they’re playing legislative limbo these days: how low can you go, when it comes to cutting income taxes? With its economy humming and unemployment rate low, Oklahoma is on course to cut the state rate to 5 percent or less—a proposal endorsed by the leaders of both House and Senate in Oklahoma City, as well as by Gov. Mary Fallin.

A few hours to the north, Gov. Sam Brownback of Kansas is pushing for a second round of tax cuts, even though last year’s cut to 4.9 percent has left lawmakers in Topeka staring at a hole in their budget. Brownback would fill the hole by eliminating most tax deductions for individuals—even the normally untouchable home mortgage deduction.

Given that many small business owners take their corporate earnings as personal income, these lower rates are intended as bait to lure employers to relocate. So neighboring Missouri is reluctantly following suit. The state Senate in Jefferson City has approved a gradual income tax rate reduction from 6 percent to 5.25 percent, to be paid for partially by increased sales and tobacco taxes.“Missouri is lagging behind,” Kansas City Republican Sen. Will Kraus warned his colleagues.

Folks with a sense of history might see this as just the latest twist in a saga of cross-border rivalry and conflict that pre-dates the Civil War. The Kansas City metro area straddles the lines separating Kansas and Missouri, and relocating a business from one state to the other can be as easy as driving a moving van across State Line Road. In recent years, Kansas has used generous tax incentives to lure such businesses as JPMorgan Retirement Plan Services and the AMC movie theater chain from the Missouri side of the line.

The income tax reductions are aimed at smaller fry, the mom-and-pop service providers and the family-owned factories that make up an important share of the mid-American economy. A recent report on economic trends in Oklahoma found, for example, that more than 20percent of the state’s economy consists of manufacturing and professional and business services. An unknown, but substantial, share of such businesses pay taxes on their earnings at the personal income tax rate—as do many privately owned banks, law firms, car dealerships, restaurants, and so on.

Critics of the tax-cut limbo dance argue that rate reductions for the ownership class are coming at the expense of funding for public schools, universities, hospitals, and other services—or they are being offset by sales and so-called “sin” taxes that fall heavily on lower-income brackets.

But the prevailing spirit in the heartland these days belongs to economist Arthur Laffer, known in some quarters as the father of supply-side theory. Laffer’s argument, influential since the days of Ronald Reagan, holds that lower income tax rates lead eventually to higher government revenues, because what is lost by cutting rates is more than made up for by the resulting burst of economic activity. One of the driving forces behind the Missouri rate reductions, St. Louis billionaire Rex Sinquefield, studied under Laffer at the University of Chicago years ago; more recently,Brownback of Kansas hired Laffer to help him design his tax policy.

In that sense, what’s going on in these states may be a laboratory for ideas pressed by Republicans in Washington. The blueprint offered this week by House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin calls for lower tax rates and fewer deductions, with the Lafferesque promise that these steps will ultimately produce new revenue to close the deficit, thanks to robust economic growth.

Not every Republican is ready to gamble everything on the theory. In Kansas, the chairman of the House committee on taxation, Richard Carlson, wants to make additional income tax cuts contingent on growth in state revenues. Future reductions would only take effect under Carlson’s proposal if the coffers in Topeka grow by at least two percent per year. Just because you believe in the magic of supply side, he seems to say, doesn’t mean you ought to bet the farm.