Rep. Todd Akin, R-Mo., speaks during a news conference on the new Health and Human Services Department abortion rule, March 21, 2012.

Politics is tribal. When a candidate commits a typical gaffe, his opponents attack while his allies mount a defense. That’s just the way it goes. But once in a while, a candidate says something so devastatingly stupid everything gets turned around. A day after Missouri congressman Todd Akin told a local TV interviewer that victims of “legitimate rape” don’t get pregnant, national Republicans called for him to abandon his challenge to Senator Claire McCaskill while Democrats welcomed the chance to fight for the pivotal seat on more favorable ground.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/fdisTOKom5I]

There are many layers of inaccuracy in Akin’s statement, but for our purposes let’s just say this: The U.S. criminal code makes no distinction between types of rape–it is simply defined as any sexual act committed without without a person’s consent or knowledge, or through coercion, physical or otherwise. And rape does lead to pregnancies–some 32,000 a year in the U.S. according to the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. There is a long history of politicians and anti-abortion activists making similar claims to Akin’s, but he has since said he was mistaken. That wasn’t enough for many in his party.

On Monday, Massachusetts Republican Scott Brown, in a tough Senate race himself, said Akin’s “statement was so far out of bounds that he should resign the nomination for U.S. Senate in Missouri.” Wisconsin Senator Ron Johnson, who is not up for re-election this year, agreed. Most importantly, John Cornyn, the head of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, asked Akin to “carefully consider what is best for him, his family [and] the Republican Party” over the next 24 hours, a not-so-subtle push to get out of the race. American Crossroads, the nation’s largest Republican super PAC, announced it is withdrawing its funds from Missouri, where it has spent millions on Akin’s effort to oust McCaskill.

Akin did not heed those calls. In a rambling interview with friendly conservative radio host Mike Huckabee during which Akin attributed his comment to “foot-in-mouth disease,” cited 9/11 and noted “I’ve even known some women who have been raped,” the candidate said he would not withdraw from the race. He apologized for his comments, acknowledged that pregnancy can result from rape and clarified that by “legitimate rape” he had meant “forcible rape,” an equally meaningless distinction under U.S. law. Things didn’t get much better in a later interview with Sean Hannity. “I had heard from medical reports that rape is such a traumatic thing that there’s a reaction,” Akin said, referring to a theory in some anti-abortion circles that the trauma of rape somehow makes a woman’s body resist conception. “But that’s wrong.” The interviews did little to quiet intra-party criticism.

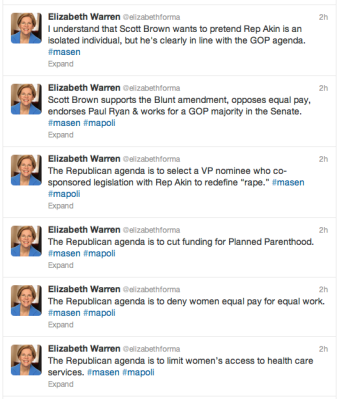

While almost all of the party’s major candidates are anti-abortion, most also support exceptions in cases of rape and incest. Mitt Romney, John McCain and George W. Bush all hold that position. Akin does not, and his clumsy defense may now be used against fellow Republicans in other races. (Last year Akin co-sponsored a bill with Republican vice presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan banning federal funds for abortions in cases of “forcible rape.” The phrase was later removed.) On Monday, Obama called Akin’s comments “offensive” and evidence that “we shouldn’t have a bunch of politicians – the majority of whom are men – making health care decisions on behalf of women.” The Twitter account of Elizabeth Warren, Scott Brown’s opponent in Massachusetts, offered a case study in spinning an individual controversy into a national issue.

While almost all of the party’s major candidates are anti-abortion, most also support exceptions in cases of rape and incest. Mitt Romney, John McCain and George W. Bush all hold that position. Akin does not, and his clumsy defense may now be used against fellow Republicans in other races. (Last year Akin co-sponsored a bill with Republican vice presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan banning federal funds for abortions in cases of “forcible rape.” The phrase was later removed.) On Monday, Obama called Akin’s comments “offensive” and evidence that “we shouldn’t have a bunch of politicians – the majority of whom are men – making health care decisions on behalf of women.” The Twitter account of Elizabeth Warren, Scott Brown’s opponent in Massachusetts, offered a case study in spinning an individual controversy into a national issue.

In a much more direct sense, Akin’s comments imperiled Republican efforts to gain a Senate majority. McCaskill, a tenacious campaigner, won office by just 2 points in the Democratic wave of 2006 and Missouri looked likely to be a key Republican pickup this cycle. Recent polling showed Akin 5 points ahead. But that lead will be difficult to maintain under the coming avalanche of Democratic attack ads and without aid from national Republicans.

That’s why outraged Democrats aren’t calling for Akin’s withdrawal–they know he’s their best bet to hold the seat. “He was nominated by the Republicans in Missouri. I will let them sort that out,” Obama said. McCaskill went as far as to say there would be blowback against Republicans if they push Akin out. “I really think that for the national party to try to come in here and dictate to the Republican primary voters that they’re going to invalidate their decision, that would be pretty radical,” she said. “I think there could be a backlash for the Republicans if they did that.”

Akin still has time to change his mind. He can withdraw without penalty before 5 p.m. Tuesday, or ask a court to remove him from the ballot after that. But after rumors circulated Monday that he might step aside–likely started by Republicans who’d prefer to see him go–Akin told Hannity “we’re going to stay in.” He posted a fundraising appeal to Twitter that read, “I am in this race to win.” Even more than tribalism, self-preservation is the way of politics.