Over at the Curious Capitalist, Steve Gandel offers an approving take on Standard & Poor’s downgrade of U.S. debt. “The ratings agency’s decision on Friday to downgrade the credit rating of the U.S. government to AA+ from AAA — stripping the U.S. of the highest rating for the first time in 70 years — was 100% correct,” he writes. In Gandel’s estimation, economic factors such as slowing growth, higher household debt and other social trends justify the ratings change.

But he also writes, “The fracturing of our political system has led to the rise of political parties that are unwilling to compromise on our biggest challenges. It is clear that the rise of the Tea Party and the pledge of Republicans in general to never raise taxes, along with the Democrats’ unwillingness to cut Social Security, produced the downgrade.” I think this is 100% incorrect.

(MORE: Standard & Poor’s Downgrades Itself)

Those might be the reasons that S&P cited in its downgrade, but that doesn’t make them legitimate. Let’s start with the tax claim. Gandel is basically saying that in the current political environment, tax increases are impossible for the foreseeable future. One gaping hole in this theory is that under the law, tax rates will revert to near Clinton-era levels if no extension of the Bush tax cuts is passed. Now, while that’s not likely, all it will take is for one Democratic President (probably in his second term) to use his veto pen sometime down the road and the Bush tax cuts will be no more.

Moreover, the distinction between taxation and spending is much blurrier than many people realize. There are a vast number of credits and exemptions in the tax code. If and when Congress takes up comprehensive tax reform — there are already plenty of proposals out there, and the debt deal’s special commission is a natural venue for discussing them — Republicans could be coaxed into talks with the promise of lower marginal rates, and in the end, they could deny that any tax expenditures excised in a deal count as tax hikes. Revenue could be increased, but rhetorically, they’d call it “closing loopholes,” not “raising taxes.”

(PHOTOS: Political Pictures of the Week)

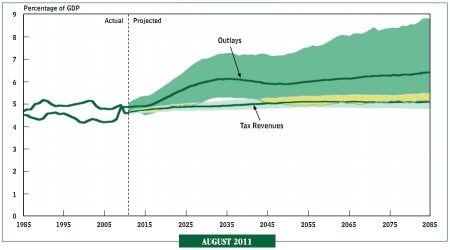

O.K., now for Social Security. It’s true that Democrats for the most part don’t want to cut Social Security. But this should have nothing to do with a downgrade because Social Security is not a significant driver of long-term deficits! The Congressional Budget Office does project a considerable gap between revenue and outlays in the next several decades (as seen in the chart below), but this is a simple balance-sheet issue. Social Security ran a surplus until very recently; small tweaks to one side of the equation or the other can correct the imbalance, and the surplus gives us some time to right the ship. It should also be noted that Democrats have flirted with Social Security changes several times in recent months, with the most prominent example being President Obama’s fiscal commission.

Now, Gandel might have meant to refer to entitlement cuts overall: not just Social Security, but Medicare and Medicaid as well. Those programs are more of a problem. While Social Security is a fixed benefit, the others pay for goods and services (medical care), the costs of which are rising at an alarming rate. Gandel listed this exact issue among the troubling long-term trends beleaguering our nation’s finances.

This brings us back to our supposedly “fracturing” political system. Hyperpartisanship was not born with the Tea Party. Though it has seen new heights of late, hyperpartisanship has been around in a myriad of forms for a long time. More important, it does not always preclude political solutions. The single largest driver of long-term deficits is Medicare. Democrats, who according to S&P will never agree to cut their most precious program, took a $500 billion chunk out of Medicare just last year when they controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House. The Affordable Care Act, which enacted those cuts, also launched a series of health care cost-control pilot programs. Many of them probably won’t work. But we’ll have a slightly better idea of how to cut costs in the coming years because of a law passed by one party alone.

(MORE: President Obama’s Economic Message Mismanagement)

Perhaps more important to the question at hand, the health care law established an underlying framework that may allow future cost shifting from government entitlement programs to U.S. citizens. Under Paul Ryan’s deep-cutting, conservative fantasy budget — and several other plans — the eligibility age for Medicare would be raised to 67. If any such plan were enacted, the health-insurance exchanges established under the new law would be the natural place for expensive-to-insure seniors no longer covered by Medicare to land.

I point this out only to make the case that Gandel and S&P are looking at a very narrow portion of U.S. political history. I’ve already made the argument that the debt-ceiling hostage scenario is not in fact bound to repeat itself ad infinitum. No matter the macroeconomic conditions, in downgrading the U.S.’s credit rating, S&P was fundamentally issuing a judgment on the ability of our political system to solve problems. The ratings agency arbitrarily pegged that judgment to the passage of $4 trillion in deficit reduction during a manufactured short-term debt crisis, and when that didn’t happen, it followed through on its threat and knocked Uncle Sam down to AA+.

(MORE: Why Congress and S&P Deserve Each Other)

I’m not one to shoot the messenger; S&P’s previous failures to recognize mortgage-backed securities for what they were have little to do with the present issue. If anything, increased skepticism of gold-plated AAA debt is probably a good thing. But I think the ratings agency’s political assessment in this case is wrong. S&P has enough of a challenge gaming out quantitative risks on Wall Street. It should leave the qualitative problems on Pennsylvania Avenue to others.