Putting a Slocum Glider into the sea during a NATO exercise.

While you were out shopping Sunday for those last-minute holiday gifts, the Navy pushed ahead with its own vision of an underwater sugar plum: a fleet of “long endurance, transoceanic gliders harvesting all energy from the ocean thermocline.”

And you thought Jules Verne died in 1905.

Fact is, the Navy has been seeking—pretty much under the surface—a way to do underwater what the Air Force has been doing in the sky: prowl stealthily for long periods of time, and gather the kind of data that could turn the tide in war.

The Navy’s goal is to send an underwater drone, which it calls a “glider,” on a roller-coaster-like path for up to five years. A fleet of them could swarm an enemy coastline, helping the Navy hunt down minefields and target enemy submarines.

Unlike their airborne cousins, Navy gliders are not powered by aviation fuel. Instead, they draw energy from the ocean’s thermocline, a pair of layers of warm water near the surface and chillier water below.

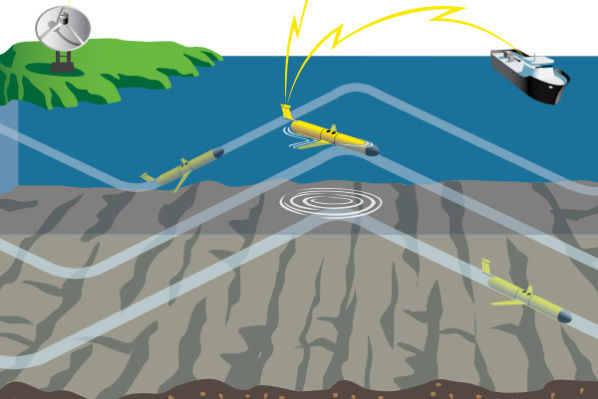

The glider changes its density, relative to the outside water, causing the 5-foot (1.5m)-long torpedo-like vehicle to either rise or sink—a process called hydraulic buoyancy. Its stubby wings translate some of that up-and-down motion into a forward speed of about a mile (1.6 km) an hour in a sawtooth pattern. As it regularly approaches the surface, an air bladder in the tail inflates to stick an antenna out of the water so it can transmit what it has learned to whatever Captain Nemo dispatched it to the depths.

Much of the work such gliders do is oceanographic in nature, collecting data about the water’s temperature, salinity, clarity, currents and eddies. Such information is critical for calibrating sonar to ensure it provides the most accurate underwater picture possible. But there are additional efforts underway to convert such data into militarily-handy information.

Slocum Gliders rise and fall as they traverse the ocean’s depths, transmitting what they learn via tail-mounted antennas that periodically break through the water’s surface.

The Navy’s Sunday contract announcement added a scant $203,731 to a contract it has with Teledyne Benthos, Inc., for continued “research efforts” into its Slocum Gliders (named for Captain Joshua Slocum, who sailed alone around the world in a 37-foot sloop between 1895 and 1898). “Carrying a wide variety of sensors, they can be programmed to patrol for weeks at a time, surfacing to transmit their data to shore while downloading new instructions at regular intervals, realizing a substantial cost savings compared to traditional surface ships,” the company’s Webb Research division says. The Webb unit is located in East Falmouth, Mass., and its Slocum Glider is the brainchild of Douglas Webb, a former researcher at the nearby Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

In 2009, the Navy issued a $56.2 million contract for up to 150 of the “Littoral Battlespace-Sensing” gliders to be delivered by 2014. The Navy has said it is investing in the field because such information could prove vital “for mine countermeasures and other tasks important to expeditionary warfare. . .ultimately reducing or eliminating the need for sailors and Marines to enter the dangerous shallow waters just off shore in order to clear mines in preparation for expeditionary operations.”

A NATO report last year examined the feasibility of launching Slocum Gliders from torpedo tubes instead of T-AGS oceanographic surveillance ships. “Operating gliders from submarines represents a step forward to embedding this technology into naval operations,” it said. “Unlike surface ships, submarines are stealth platforms that could transit denied areas while releasing a glider fleet.”

Navy Captain Walt Luthiger, a submariner, said an exercise using such gliders proved their mettle in yet another arena. “The environmental information provided by the gliders has proved valuable,” he told NATO public affairs in 2011, “and helped everyone in that very difficult job of finding submarines that don’t want to be found.”